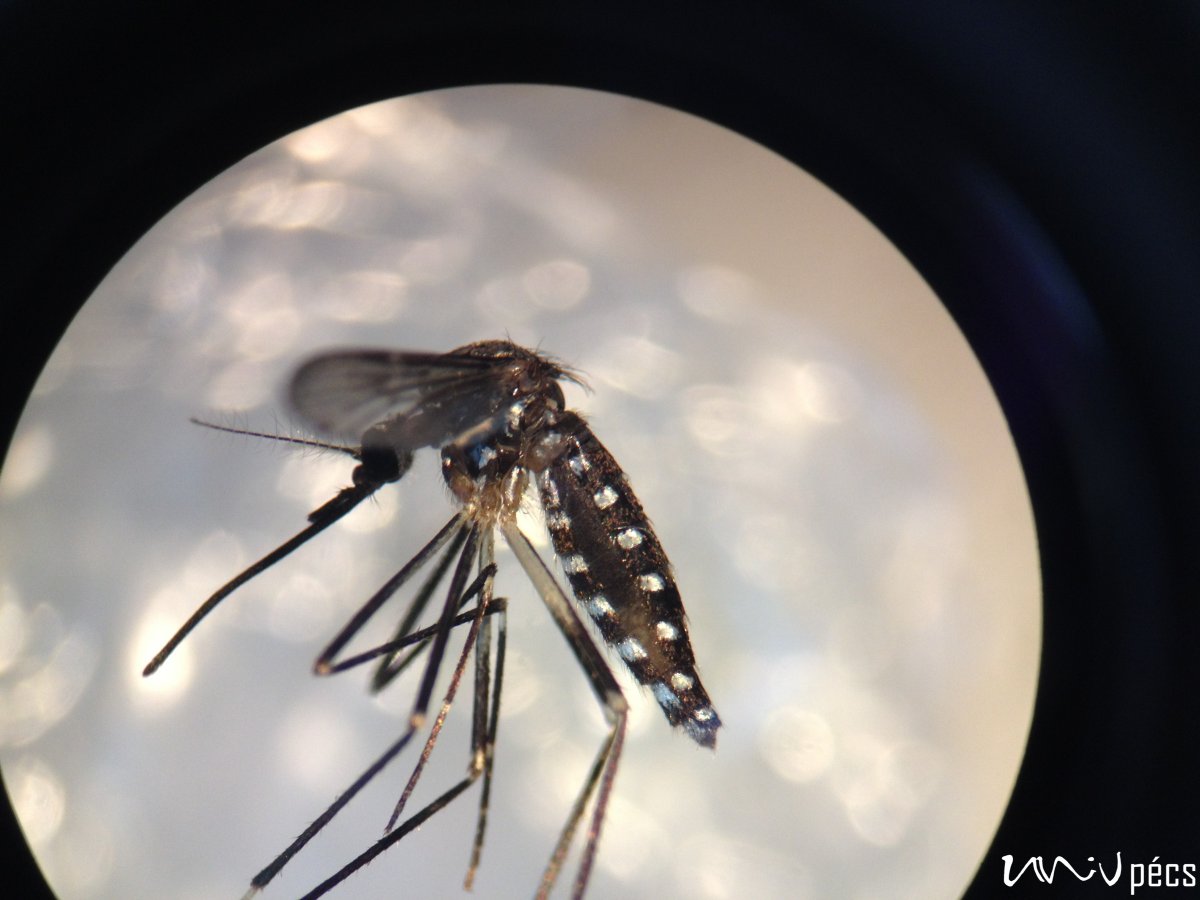

LIKE THE SILVER STRIPES OF A MOSQUITO

2024. March 16.

Kornélia Kurucz, Assistant Professor at the UP Faculty of Sciences is a member of the Szentágothai János Research Center’s virology research team. More specifically, she works with mosquitoes. In the past couple of decades, foreign species capable of transmitting tropical diseases have appeared in the temperate climatic zone.

As an effect of the climate change, do mosquitos travel north on their own?

In the case of mosquitoes, the gradual migration to northern regions is not so typical. The appearance of foreign invasive mosquito species in Europe can in all cases be attributed to human activity; we usually bring their eggs in with trade or tourism.

On which surfaces can eggs survive?

Inside a tire or on a truck’s tarp. These eggs can survive for a long time; they can tolerate drought and heat as well; they are very resistant. As soon as an egg gets some water, larvae rapidly hatch; they only need two or three weeks to fully develop. Those species, which get accidentally brought here from Asia or Africa can survive the winter in their egg form. Invasive species are usually able to quickly and easily adapt to their new environments. Thanks to climate change, our weather conditions are not so different from Asia’s climate anymore; our winters are not harsh enough for the mosquitoes to perish during them. The first of these mosquito species appeared in Europe in the ‘60s, but this process has been getting faster and faster ever since.

How are invasive vs. indigenous mosquito species different?

Invasive species are better at survival. They are not picky. They have a higher tolerance to draught, cold and heat. While indigenous mosquitoes get decimated by an Easter frost or a draught in August, the Korean ones are not so sensitive. In addition, unlike the local mosquitoes, which are active and suck blood at night or early dawn, invasive species stay active during the day. This is important, because perhaps we should rethink our defense against them.

Are the itchier mosquito bites committed by “evil” mosquitoes? Do we need to be afraid of these new species?

That the mosquito bite swells up is more of a question of personal sensitivity. Many people are discussing how the bites of the invasive species hurt more. Our immune system’s reaction might be more intensive against a previously unknown species. Their bites are not more dangerous than the indigenous ones’ in this sense. As far as pathogens are concerned, that is only partly the case.

Mosquitoes coming from the tropics could bring different types of exotic pathogens with them or they could transmit local pathogens more effectively. In this sense, yes, they are more “evil”.

Infections transmitted by vectors (such as mosquitoes) are complex; multiple conditions have to be met at the same time: for example, the pathogen must be present in the environment and the mosquito must be a suitable host for transmitting it. Not all mosquito species can transmit all diseases. In order to spread a disease among humans, the mosquito must feed off humans – this is not true for each of the fifty mosquito species living in Hungary. That means that it is not sufficient to bite infected hosts (either animals or humans). However, if the pathogen can reproduce inside the mosquito, they can transmit it to their next victims (for example humans) or the next generation of mosquitoes through the eggs.

How can we best react?

It is the job of epidemiologists to constantly monitor the foreign or indigenous new mosquito species, which could potentially pose a medical risk to humans in order to provide up-to-date information about the spread of pathogens and invasive mosquito species within the country. This would be the first step towards effective protection and the prevention of infection. We cannot plan aimed interventions or protective measures without them.

On another note, the local population can do a lot more than they would think!

We should try to avoid getting bitten. By paying a little attention, we could eliminate the mosquitoes’ breeding grounds around the house (small water-spots, containers filled with stale water, rainwater gathering barrels, clogged gutters, etc.).

What kinds of diseases can mosquitoes transmit?

We have to prepare ourselves for the emergence of tropical viruses. The first thing to come to mind is perhaps malaria: it claimed a lot of victims in the last century, however, we have successfully eliminated it within Europe. Its host, a subspecies of anopheles, still lives among us, the pathogen (Plasmodium) however is not present. We do not have to worry about it until it gets reintroduced to the environment.

We should rather be more concerned about Chikungunya virus (which causes raging fevers and strong muscular pain), West Nile virus (in more serious cases can affect the nervous system) or even the Dengue virus (has symptoms similar to influenza, causes emesis, diarrhea, rashes and joint pain). The Chikungunya virus originally was indigenous to Africa, however, today it can be found in every tropical or subtropical climate zone, within Europe it has caused epidemics in both Italy and France. The West Nile virus as of today can be found all around the world and it is considered to be indigenous to Europe as well, even Hungary is no exception. We have seen Dengue virus outbreaks as well (Greece and Madeira) – however, we are not at considerable risk here in Hungary. Many people fear the Zika virus above all else. Outside of its original range of transmission it only caused serious problems in America, it was only brought to Europe by a couple of tourists.

These viruses cannot spread from human to human, in all cases they need a vector-organism: mosquitoes.

If someone, who is infected with the Zika virus is bit by a mosquito, which can transmit the disease in Europe, and then that mosquito bites another human, there is a chance for this chain to continue. The more people are bitten by these mosquitoes the larger the chance of an outbreak is. The Zika virus and the Dengue fever are on our doorstep. They could both survive in Europe, the mosquitoes capable of transmitting them are already here…

How many invasive mosquito species have settled in and around Pécs?

We identified six invasive foreign mosquito species in Europe so far; out of those Asian tiger mosquitoes (Aedes albopictus), Asian bush mosquitoes (Aedes japonicus) and Korean mosquitoes (Aedes koreicus) are known to live in Hungary, there might be more, which are yet to be identified. All three of these species can be found in the Southern Transdanubia. In Pécs, Korean mosquitoes are more common, while Asian bush mosquitoes are more common south of the city, near the Croatian border.

As of this year, they are no longer spraying the mosquitoes with planes.

What is happening nowadays is closer to eradication than suppression. Because of climate change, draughts and chemicals, insect populations are diminishing… and the spraying mosquitoes does not help either. The prohibition of aerial spraying is the result of EU regulations, the active agent of the chemical stayed the same, it is only dispersed with fog machines on land vehicles; instead of it falling from above it forms a fog at shrub level which lingers longer.

As a scientist, do you agree with the extermination of mosquitoes?

We must control the population of mosquitoes, however, it is clear that mosquitoes, just like other flying insects, play an important role in our ecosystem so we should not exterminate them, we should only talk about controlling their population.

We must find a healthy balance.

We have two main options for mosquito control: we can either decrease the number of flying mosquitoes or their larvae in the water. If we can find the water source, which serves as their breeding grounds, we can manage the localized suppression of the larvae and we can get rid of ten thousand mosquitoes with a minor investment and we can prevent the transmission of diseases. If we let them hatch, and fly away, then we can fly around trying to catch all ten thousand of the (potentially infected) mosquitoes. The only way to kill them then is to use the chemical fog, which is a non-selective insect neurotoxin (deltamethrin), meaning that it kills every flying insect it comes in contact with not just the mosquitoes. One particular study, which states that after each spraying only 1% of the insects killed are mosquitoes the remaining 99% percent consists of other flying insect species, is the topic of much debate.

The biological control targets the larvae in the water: this utilizes a naturally occurring bacterium protein, this is much more selective than the chemical procedure.

I can see that you are not a fan of this method either. What would be a good solution?

There is no perfect solution. Artificially intervening into nature is never without its consequences.

Researchers thought that the biological method was a miracle cure at first; now not so much. The aquatic mosquito larvae are a part of the aquatic ecosystem as well; they are an important food source so we cannot kill them mindlessly. We must explore the waters where the larvae are, like river floodplains, which is meticulous cartographical work, not to mention puddles and sever junctions… Even some water standing in a wheelbarrow could be enough. An urban larvae control cannot be organized only centrally without the citizens cooperation – comparatively, using the neurotoxin is much easier.

What should we do then? Shall we leave it to nature?

That is not it either. Bats and swallows are not enough.

We should not forget that we have to control mosquitoes primarily because of their pathogens not because they are a nuisance.

In most European countries, they are killed in order to prevent an outbreak, not because their bite hurts, or their buzzing is annoying us while we are drinking beer on the shore of Lake Balaton. Here this is not part of our culture. In Pécs, the number of mosquitoes above which we must take action is 20 mosquitoes in one night in one trap. This number is low. The population is unsatisfied nonetheless. In Serbia or Austria this number is 100. The threshold-level is different.

What do you suggest?

Insect repellent spray, window screens. And prevention! We can do a lot as individuals.